Over and over again, I’ve complained about the paucity of good studies on pedophiles. Yes, there are researchers working in this area, and I’m so glad for their work… but it’s really, really hard. Who wants to fund researching the psychology of pedophiles? Besides, even with funding, it’s almost impossible to get a good, unbiased sample of people to study. You can’t walk up to someone on the street and be like, “hey, are you a pedophile, want to come to my lab?” You can study convicted child molesters, but that’s not representative of pedophiles. Try to do a survey for pedophiles online, and you get… those who are in online pedophile spaces who are also bold enough to take a survey that admits their attraction. Again, just a really biased sample: Anyone in these spaces is looking for something, be it support for their troubles or sexual fantasies, and their responses might not match the general population.

So I was thrilled to learn about the research being done by Aella on kinks. Now, Aella is not a professor and doesn’t have a PhD, but that allows her to push the boundaries a bit and try unconventional methods; those methods are well thought out and she has the tools to reach a different sample than academics would.

She was like, “what’s the problem with surveys on kinks?” And the fundamental problem she identified was sample bias: reach out to a particular group, and you get the die-hards, or the people who have A Reason to be in that space, but you don’t get the people who are chill, more like, “yeah, I’ve got that kink.” So her philosophy was instead: make a general survey and just BLAST it out. Get a lot of people to take it and to indicate their kinks over a huge spectrum of possibilities. With clever design and a large social media following, she got well over 600,000 responses, and she asked about attraction to children. So from the perspective of studying people like me, the strategy was, “let’s recruit everywhere, and some of the people will happen to be pedophiles, and so we’ll get a less biased sample.”

It’s not perfect; it’s obviously still selecting for people willing to fill out a long survey with an interest in kink, and that’s going to screen for certain personality traits and self identities. People are much more likely to hear about it if they’re kinky and at least somewhat open to kink communities. Nonetheless, it’s such a different sample from anything I’ve seen before that it might really have some compelling insights.

So that’s the methodology of her survey: get literally hundreds of thousands of responses, and then dig down. The survey catches thousands of people who indicate a sexual interest in kids, and we can analyze them and, hopefully, better understand pedophiles. Seriously, I’m so excited about this.

That doesn’t mean I’m going to take it uncritically, though. I want to dig in, provide context, think about alternate explanations for the results, and in general contribute to understanding just what the heck is going on. This post is going to really dive in, so buckle up. We’ll walk through Aella’s results. Why did it come out this way? What does each result tell us?

I hope it’s of interest to everyone who wants to better understand pedophiles. Perhaps my thinking will also be a resource to researchers who want to ask better questions and derive more results. This is a good time to make an offer: If any researchers are out there and want thoughtful feedback on their survey design or analysis before sending it out, I am more than happy to provide it.

I recommend reading Aella’s post about pedophilia first, and then coming back here for my analysis. My post can be read on its own, because I will repeat the key results I’m commenting on, but you will have more context and details if you’ve read Aella’s first.

Also, this post is long and detailed. There are even footnotes! I think it’s a relatively light read for what it is, but it is unapologetically about data, so be prepared.

So who’s filling this survey out?

Any survey is subject to bias if it’s not given to a representative sample of people.

If you ask people at the beach if they like the feeling of sand between their toes, they’re much more likely to say yes than the average person—after all, they chose to go to the beach! It won’t be 100%, of course. Some people like swimming or sun or the smell of the ocean enough that they’ll go even though they don’t like sand. But it’s still not a representative sample: there’s what’s called a “systematic bias” towards people who like sand among beachgoers, so your survey would give the wrong result.

The source of bias can also be much more subtle. Ask people the same question but at a hotel in Miami, and a lot of those people will be tourists who decided to go to a beach city, so they’re also going to be more likely than average to like sand. (The bias will probably be less, just because there are lots of reasons to go to Miami other than the beach.) Now ask that same question but at a hotel in New York City, and you’ll be getting people who decided to take a vacation to a non-beach town: the answer you get will probably be a bit lower than average. There’ll be some sand-lovers, but fewer than in the general population. Neither sample is representative.

Aella has this in mind. She knew that advertising to any one kink community would bias the results, so she decided to go for a wide reach: try to get as many people as possible to fill it out. A large sample is no guarantee that it will be free of bias (after all, survey everyone in Miami and you’ll have a lot of responses, but there’ll probably still be an above-average appreciation of sand), but the hope is that the method Aella used provides unbiased samples for any particular kink because it’s not based around finding people with that kink. She’s not surveying Miami; she’s surveying a whole bunch of cities across the US, and she’s asking about sand and Broadway plays and Dollywood and if people think the world’s largest ball of twine is a fun tourist attraction and hopefully it all washes out. [1]

Are we sure there won’t be a bias? No. After all, if you sample a lot of cities across the US, you’re still missing the rural and suburban population, and maybe there are differences in how much people like sand (or twine…) across those locations. But it’s promising: I can’t think of why there’d be a difference.

OK, so back to Aella’s survey. For our purposes, the idea is that most of the pedophiles who took the survey didn’t find it because they are pedophiles. So we hope, like with the cities, that the kinds of pedophiles who took it are representative of pedophiles everywhere.

Is this reasonable? Well, Aella seems to have initially publicized the survey via her social media, although it then spread on its own. Her social media seems to involve a lot of discussion about sex (which… she studies sex, so reasonable!) and so, while no specific kink was targeted, it was probably taken largely by highly-online people who are in some kink community. (Otherwise, people weren’t that likely to even find it, let alone be interested in it.) Let me put it this way: it was probably advertised in foot fetish communities, but not on most board games communities.

As a result of its novelty, her thoughtful design, and her social media reach, the survey had a huge, almost absurd reach, with well over 500,000 responses.

So is it going to be a representative sample?

The obvious biases to those responses are listed by Aella herself: “Most respondents are in their early 20s, and around 70% of respondents are women — a reflection of the demographics that most love taking internet surveys (as verified by my friend who runs one of the oldest, biggest personality-testing websites on the internet).” Which, fine; just like surveying only city dwellers about sand, this is a bias but it doesn’t necessarily mean that responses about kinks won’t generalize, especially if we consider men and women separately. We don’t have any reason to think that younger respondents would give different answers. (They might! We just don’t know.)

What about for pedophiles? Let me tell you, getting a representative sample of pedophiles is basically impossible. (Researchers seem to either use convicted child molesters, an obviously biased sample, or else advertise on forums which is only going to get those who engage online in pedophile spaces.) Aella’s effort is the best I’ve seen at getting around these challenges, but unfortunately this is a hard problems and some potential biases still exist.

To illustrate the potential source of bias, it’s worth noting that I only heard about this survey recently, and primarily because a friend found out about it and forwarded it to me. That friend happened to know about my attractions. It wasn’t widely advertised in pedophile spaces; it was advertised in kink spaces. And it’s a fundamentally different kind of pedophile who goes to kink spaces.

I didn’t even have any sex until I was 30 years old, and it would be many years before I had sex again. I didn’t know what a “bear” was in gay culture until I was about 35. Why would I visit a website about sex, or kinks? To this day, my friends think of me as innocent and unaware of common sexual terms. That turns out to be far from the truth, but I keep up the act because I couldn’t explain how I learned them when I so obviously don’t have sex.

The point being: a pedophile who is ashamed of their sexuality, who has no attraction to adults, who tries to run away from who they are… they’re not going to find this survey. Is the guy from a conservative Christian family going to run across it? What about the person who tries to repress and ignore their desires, and not engage online? What about the person who’s attracted to kids, fantasizes about nice non-kinky relationships with them, knows it can’t happen and just lives their life?

So yes, pedophiles who are exclusively attracted to children, or those who are ashamed of their attraction, or those who repress their desires and pretend they’re not there, or those who have no draw to kink are all likely to be seriously underrepresented on this survey. As we look at the results, we have to remember that even this huge sample may not be representative.

Diving in: interpreting the data

How many pedophiles are there?

Aella finds that 3.5% of men, and 0.6% of women indicate some sexual arousal from children. These numbers are broadly in line with other findings.

Do I believe those stats? Well, I have no particular reason to doubt them, but there are a few methodological concerns to point out that suggest these numbers might be a bit low.

- Pedophiles, especially those who are exclusively attracted to children, may be underrepresented in this sample. Again, because it was advertised primarily to kink communities, people like me who have exclusive sexual interest in children wouldn’t find it.

- Pedophiles who haven’t discussed their attraction with others (e.g. on a supportive online forum) may be especially wary to disclose their attraction, even in what might feel like an anonymous online survey.

- Pedophiles who have repressed their desires and are “lying to themselves” about their attractions are more likely to deny the attraction. Most of the respondents in the survey were in their early 20’s. I know people who only admitted to themselves that they were pedophiles after age 26. This also suggests a bias in responses.

I want to take a moment on that third point, the age question. My hypothesis, that many people don’t admit their pedophilia to themselves until later, is backed up by Aella’s own data: the average age of males who said they didn’t find children arousing was much lower than the average age for males who admitted an arousal. (This trend was less clear for females, where the average age for all categories was between 21 and 22 years old.) In the rest of the survey, Aella only analyzes data for people between the age of 19 and 26, and I would like to know if responses differ among the older age groups.

Now let me be annoying: there are also reasons to believe the percentages Aella finds are too high! (Do you hate me yet?) For one thing, maybe kinksters are more likely to be attracted to children than other people, because they already have sexual desires that run outside the usual. (“Weird correlates with weird,” as Aella herself says.)

Additionally, Aella’s question about pedophilia may cause positive responses to be overstated. The question is: How arousing do you find children?” with six possible responses: “not arousing,” “slightly arousing,” “somewhat arousing,” “moderately arousing,” “very arousing,” and “extremely arousing.” My concern is that people might select “slightly arousing” when they don’t really have a strong attraction to children. Maybe they saw some beauty pageant and were kind-of turned on, but let’s just be real, they’re not pedophiles. Or maybe they’re not attracted to kids, but they’re attracted to taboo or even to a sexual experience they had as kids. (We’ll discuss this more later.)

What I wish is that the scale had been more like:

- Not at all arousing

- Slightly arousing, but much less so than adults

- Arousing, but somewhat less than adults

- About as arousing as adults

- Somewhat more arousing than adults

- Much more arousing than adults

This comparison would make it much easier to identify those with a “significant” interest in kids, and might force people to be a bit more honest in their self-appraisals. (Honestly, I would edit these questions even more if I were really diving into pedophilia.)

This phrasing might also shed more light on questions like “How many people have you had sex with?” Exclusive pedophiles will give very different answers than non-exclusive ones, and I’d like to see that data.

So are Aella’s numbers good? They match what others have found. Even if I might’ve preferred some tweaks to the approach, it helps to inspire confidence that the numbers line up in a broad sense. Nonetheless, there are a lot of questions remaining, and I’m not sure anyone has “the right” number for how many people are pedophiles.

And that’s just asking “how many are there?” If that question is so hard, imagine all the others!

Impact of consuming erotic content about children

I’m not surprised that the vast majority of pedophiles said that consuming erotic content of children would either reduce or have no effect on their likelihood of offending. It matches my own views, and what I believe research supports.

Just because I agree, though, doesn’t mean that I don’t want to carefully review the methodology. This is a place where I think the validity is really impacted by limiting the analysis to younger pedophiles. I can’t help but wonder what older pedophiles (like me!) would have said. We’ve had more time to see the impact of erotica on our interests. While I don’t think the answer would be any different, having this answer primarily from young people seems like a real opportunity for bias if I were being critical of the data.

Finally, something Aella wrote struck me. “It looks like the vast majority of people reporting pedophilic inclinations say that consuming child porn would either reduce their urges to act on it, or have no effect.” That’s not what I took away from this question at all! To me, “erotic content about children” includes, and is primarily, drawn work, computer renders, stories, and perhaps AI. “Artificial child pornography,” as I’ve called it in the past. If this had been about real child porn, my answer would’ve been quite different.

In fact, pedophiles who didn’t know about artificial child pornography might have had quite a different point of view, which might have skewed the answers as well. Precision in questions like this really matters. What would the answers have been if there was one question about real child pornography, and another about artificial child pornography?

Weird correlates with weird

Aella finds that pedophilia correlates with… well, a lot of things that are small minorities of the population. Queerness, polyamory, mental illnesses, even extreme body weight (at either end of the scale). I actually almost wish she’d asked about IQ; I’ve always had a theory that pedophilia is overrepresented at both low and high IQ. In other words, I have a suspicion that things that are “unusual” brain functioning tend to overlap with each other.

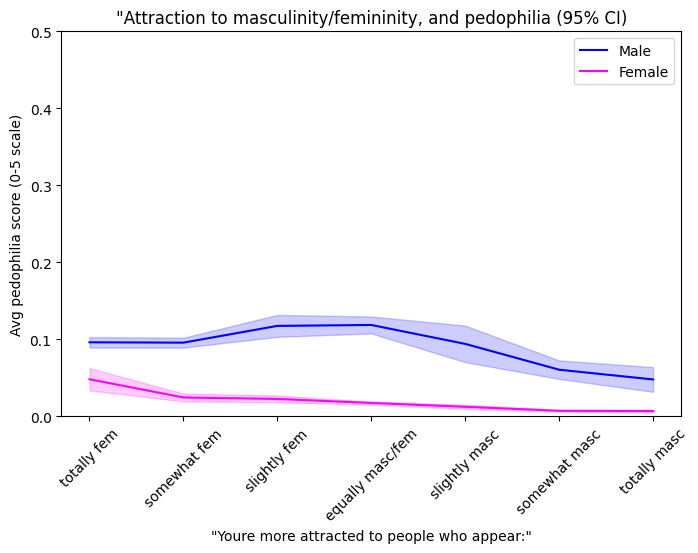

Let’s take a moment to address gender and sexual orientation, and especially the breakdown into “gay or straight” pedophiles. [2] This issue is complex and I think the survey’s questions are not strong enough to break it down. Here are the charts Aella presents:

I really appreciate the spectrum identified here, and the questions about both presentation and genitalia. But unfortunately, we pedos are a complicated bunch.

Content warning: The rest of this section is blunt about sexual attraction to children.

For example, I have male friends who are attracted to adult females and prepubescent boys. Or, for that matter, attracted to adult females but both boys and girls if prepubescent. How should someone like that answer the questions Aella proposed about attraction? Especially since this question isn’t in a section that is about pedophilia.

Or consider my situation. I’m not attracted to boys who are “masculine” in the sense of, say, very muscled. I’m attracted to boys who are, well, boyish. Not feminine, not adult masculine, but boyish. That’s not an option for me on this survey, and so I don’t know what to mark. Maybe “somewhat masc?” I dunno.

And y’know what? I’m actually pretty simple compared to others! When I look online, I see lots of people who are attracted to, say, young boys who present more feminine, or to the fantasy of taking a young boy and “feminizing” him, but they’re not attracted to girls or women. What should they select? And will that change if they are counted as “gay” or not?

Now, some of these concerns are just minor quibbles, but a “gay” pedophile is a more complicated concept than you might think, especially when attractions differ towards adults and children.

Now, consider Aella’s comment: “Bi men are more pedophilic than gay men, but gay women are more pedophilic than bi women?? Weird.” I think this might be looking at it the wrong way.

From a statistical perspective: Is it that bi men are “more pedophilic,” or is it that pedophiles might be more likely than average to have attraction to both genders as children but not adults? There are, after all, “straight” men attracted to adult women… but both girls and boys. (Since at a young age, they’re more similar than they are different.)

Alternately, perhaps it’s common for pedophiles to have differing attractions for pre- and post-puberty. Maybe they’re attracted to adult women and pre-pubescent boys, or adult men and pre-pubescent girls. Are they “bi” if so? What about my friends who are only attracted to adult women… except they fantasize about being a boy getting abused by a man? They don’t want to have sex with a man.

I have a lot less context for female pedophiles. I do wonder how many of those who are attracted to girls might be trans women, given how the statistics were diced. Another possibility is that women are imagining themselves as children. That said, I don’t have the right perspective to add much, at least without breaking down the stats more.

However, the statistic I really want is one that analyzes adult and child attractions separately. Is it the case that men who are “bi for adults” are more pedophilic than men who are “gay for adults”? I can’t tell, but that would help us parse through much of these questions.

Sexual Assault: Does being a victim make you more likely to be attracted to children?

OK. These are maybe among the biggest questions that surround pedophilia. Are you more likely to be a pedophile if you were sexually assaulted as a child? Are you more likely to commit sexual assault if you are a pedophile?

Let me start by sharing some anecdotes. I often RP with other adults online who want to play boys, and I will ask them why they’re interested in it. Some will describe having had sex as children. On forums that deal with these kinds of issues, there are people who describe sexual experiences they had as kids. It does feel like the incidence rate of childhood sex is higher among people who are interested in boys.

Not surprisingly, Aella’s survey bears this out. Jumping ahead to the portion on childhood sexual abuse, she finds that among males, 7% who were sexually assaulted report pedophilic interest, while only 3% of those who were not assaulted report pedophilic interest. Among females, those numbers are 1.2% and 0.4%.

What should we make of this?

Well, first of all, those numbers are low in both cases. I have heard fears that being assaulted in childhood “makes” you a pedophile, and yet 93% of the time for men, and 98.8% of the time for women, that’s not true! The vast majority of childhood victims never develop pedophilia. So let’s just clear that one up right away.

Should our conclusion be that childhood sexual assault does make one more likely to be a pedophile? Well… maaaaaybe. There’s even a convenient explanation for why: the early sexual experience “fixates” someone on childhood sex, and that fixation then leads to the attraction to children.

But correlation is not causation. Just off the top of my head, here are three other hypotheses we should consider:

- You’re very likely to be the victim of childhood sexual assault from a family member. Perhaps pedophilia is genetic, and if a family member assaulted you, you’re also more likely to inherit it.

- Perhaps the same psychological elements that predispose you towards pedophilia also predispose you to other characteristics that make you vulnerable to sexual assault (such as mental illness) and that is skewing these statistics. (We might have the data to answer this: take the same stats, but controlled for mental illness.)

- Perhaps there is a correlation between those willing to disclose something as personal as childhood sexual abuse, and disclosing something as vilified as pedophilia. Maybe there’s no real-world connection at all, and it’s all about willingness to share!

Are you still sure that childhood sexual abuse “causes” pedophilia? I have at least some doubt. I suspect there might be some causation, but I wouldn’t bet on it. Not without better studies.

One final quibble about these numbers: I wonder if they might be a little bit low! I know of people who look back on childhood sexual experiences positively. (Make of this what you will; I’m just reporting what they tell me.) Aella’s question was about “sexual assault;” maybe they wouldn’t classify it that way. In fact, the classifications of sexual assault that Aella uses (none, mild, moderate, and severe) are all in the eye of the beholder, and another hypothesis might be that it is one’s perception of the encounter that influences later pedophilic desires. Maybe someone who thinks they saw their swim coach looking at them fixates on that moment for the rest of their life… while someone who is actually sexually assaulted moves right past it.

You might be sad, reading this, that I am raising more questions rather than providing answers. That’s the nature of this work, unfortunately, at this stage of research. I’m just glad Aella gave us enough meat to really dig in!

Now, those aren’t the only sexual assault statistics that Aella discusses. She also finds that:

A. Those who are victims of sexual assault as adults are more likely to have pedophilic leanings, and

B. Perpetrators of sexual assault are more likely to be pedophiles.

Point B is the bombshell, and while Aella acknowledges the effect size, she doesn’t talk about its implications. But the implications are dire. The whole point of my blog is that people like me should be treated as people and not prejudged, but if so many pedophiles are committing assault, then can I really stand by that claim? This post has to deal with that question, and I will, right after this message from our sponsors… no, sorry, no sponsors on my pedophile blog. Rather, I want to talk about Point A first, because I think it’s instructive when we look at Point B.

Why? Because Point A makes very little sense if you think about it! Why would being the victim of sexual assault as an adult make you more likely to be sexually attracted to children? I can’t think of any reasonable mechanism where being assaulted would cause you to develop attraction to children. (Although I will note that the effect is quite small among women; it is primarily a phenomenon among men.)

Let’s dig into this question, to see if it reveals something about the data overall.

Above, I proposed three explanations for why sexual assault as a child might be correlated to pedophilic attraction without causing it. Two of those apply almost verbatim to sexual assault as an adult, so I’ll copy them here with mild edits, and I’ll add in a third possibility below those two:

- Perhaps the same psychological elements that predispose you towards pedophilia also predispose you to other characteristics that make you vulnerable to sexual assault (such as mental illness) and that is skewing these statistics. (As before, I’d love to see these stats, but controlled for mental illness.)

- Perhaps there is a correlation between those willing to disclose something as personal as sexual abuse, and disclosing something as vilified as pedophilia.

- Perhaps victims of childhood sexual assault are also more likely to be victims of adulthood sexual assault, and all we’re seeing here is the “shadow” cause-and-effect of childhood sexual abuse.

(It would be helpful to see the chart for adulthood sexual assault, but only among those who reported no sexual assault as children. That would at least help eliminate the third possibility!)

Let’s say that you agree with me that being sexually assaulted as an adult is not going to make you suddenly develop an attraction to children. Then maybe the actual impact of childhood sexual assault is smaller than we thought. Looking at the two charts for adulthood sexual assault and childhood sexual assault:

They look very similar. They’re actually more similar than they look, because the y-axis scales are different in a way that makes the childhood effect look a lot bigger than it is! (It is bigger, but only very slightly.) My best guess is that being the victim of sexual assault as an adult does not cause you to be any more likely to develop pedophilia, and some of the other mechanisms I proposed might be at play to cause this correlation. That implies that, at the least, childhood sexual assault is somewhat less of a cause than the chart suggests.

But Point B. Oh my, Point B. Are pedophiles more likely to commit sexual assault? This one is so big that it gets its own section.

Sexual Assault: Are pedophiles more likely to commit sexual assault?

Let’s not beat around the bush. Look at the money chart:

From eyeballing this chart: 3% of people who say they’ve never committed sexual assault indicate at least some arousal from children; around 28% of those who committed “extreme” sexual assault say the same. 28%!! [3]

That’s wild. Pedophiles are way, way overrepresented among those who commit sexual assault.

Now, while this chart tells us what percentage of sexual assaulters are pedophiles, it doesn’t tell us what percentage of pedophiles commit sexual assault. This is an important difference! If there are few sexual abusers overall, then it’s still true that most pedophiles do not commit sexual assault.

It also doesn’t tell us if that sexual assault is committed against children or adults.

But boy oh boy does this chart raise questions. And the worst-case interpretation is pretty bad: “Doesn’t this suggest,” someone might ask, “that pedophiles are more likely to sexually assault others? Do pedophiles, seeking sexual satisfaction, molest kids at especially high rates? Sure, not all pedophiles, but a lot?”

We don’t have the data to disprove that claim. We don’t have the data to prove it, either. But this is suggestive, and in a worrying direction.

And yet, we should be careful before we draw a conclusion. There are several deep dives that might reveal something else going on.

Deep dive 1: Maybe it’s not about the pedophilia. Remember how adult victims of sexual assault were more likely to be pedophiles, and that didn’t make sense? One way to explain it that I proposed was: “Perhaps the same psychological elements that predispose you towards pedophilia also predispose you to other characteristics that make you vulnerable to sexual assault (such as mental illness) and that is skewing these statistics. (As before, I’d love to see these stats, but controlled for mental illness.)” The same thing applies here: maybe those other psychological elements predispose you to perpetrating sexual assault. Sociopaths are, according to Aella’s data, much more likely to be pedophiles, so maybe it’s not “really” about the pedophilia at all.

Deep dive 2: Maybe it’s about willingness to disclose. Again from discussing the relationship between being a victim of sexual assault and pedophilia: “Perhaps there is a correlation between those willing to disclose something as personal as sexual abuse, and disclosing something as vilified as pedophilia.” Maybe those who are willing to disclose they committed sexual assault are also more willing to admit to being attracted to children, and if we got “honest” answers from everyone we wouldn’t see the same phenomenon. This question—are we just picking up on willingness to disclose—is something that could be underlying much of this data. (Perhaps we could ask about a non-sexual crime, like robbery or drug abuse, and see if there is a similar correlation.)

Deep dive 3: Maybe we don’t understand what we mean by pedophilia. So far in this blog post, I’ve avoided a very important limitation of the survey’s definition of pedophilia. Quite simply: I think the question identifying pedophiles catches people who are not really pedophiles.

As a reminder, Aella asked: “I find older children who have not yet reached sexual maturity (e.g. age 8) to be:” and then allowed people to select options from “not arousing” (0) to “extremely arousing” (5).

Let me give examples of people I’ve met in pedophile spaces who would answer yes to this question.

- People who are attracted to taboo things. They’re not attracted to children’s bodies per se; they like anything that is taboo.

- People who are attracted to power differences, but not to children. They find the idea of sex between adults and children arousing because it manifests such a strong power difference.

- People who had sexual experiences as children, and who find it hot, without finding children’s specific bodies attractive.

- People who were gripped with a “what if” thought from their childhood, whose parents and teachers warned them about child molesters and who gripped onto that warning.

- People who enjoy the idea of being a child in a sexual situation, but are not attracted to children’s bodies.

Are any of these people pedophiles? None of them are physically attracted to kids. They might all answer affirmatively to the question Aella asks that is meant to assess pedophilia, depending on how they interpret finding children arousing.

Deep Dive 4: Maybe people overestimate the extremity of abuses against children. I have gotten emails in a panic because someone’s nephew sat on their lap and they got an erection, and they worry the child felt it and was scarred for life. Another person returned a child’s kiss and worried that it was assault. This is not to minimize these situations; there’s a lot of complicated moral questions to discuss in each of them. However, how “extreme” something is really is in the eye of the beholder.

Now, let’s be clear. These deep dives raise questions, but after reading Aella’s survey, I can’t deny that my priors on “pedophiles are more likely to commit sexual assault than non-pedophiles” haven’t gone up. It’s impossible to look at this data and not revise one’s views to consider that maybe pedophiles are more likely to commit assault. I’d really love more research into this, because this goes right to the heart of my blog.

Age of sexual activity

Aella has some great data showing that those who started masturbating early are more likely to have pedophilic attraction, even when you subtract out victims of childhood sexual assault. (I am very grateful for the data when you subtract out victims of childhood sexual assault!)

Now, let me tell a story about friends who are into BDSM. Most of them have stories about how as kids, they gravitated to superhero stories or similar where people got tied up. Robin having to be saved by Batman in the old Adam West series is a particular favorite. Did this childhood exposure cause them to become interested in BDSM, or did a pre-existing interest in BDSM lead them to latch on to this, or are they retrospectively perceiving their past differently?

Of course, the same question arises here. Did people start masturbating early because their brain was already wired a certain way, or did the discovery of masturbation make them more sexually interested in children? It might even be that people remember the childhood masturbation better because they thought about it more once they realized their attractions. It’s very hard to tell!

Moreover, even among those who started masturbating at age 4, the average pedophilia score (among men) is like 0.3, which still means the vast majority have no attraction to children.

Finally, Aella subtracts out those who were victims of childhood sexual assault, but that is in the eye of the beholder. What about childhood sexual experiences that people don’t classify as assault? In the gay community, there are also lots of stories (especially among older men) of having started cruising at a very young age. I’ve talked to people who had sexual experiences as kids with adults that they do not perceive as assault. What about older children with younger children? We might consider all of these assault, but the “victim” might not. So when we look at the stats of those who were not “sexually assaulted” it’s important to remember that this isn’t a tight definition. [4]

Finally, I feel like it’s worth sharing my own story. I am exclusively attracted to boys, and very strongly. I didn’t start masturbating until age 13, and did not have sex until 30. So on this data, I am an outlier!

What about that bit where pedophiles are more interested in grief, disgust, and despair?

Aella posts some very interesting charts where people are asked what emotions are erotic in either others, or themselves. Those enjoy enjoy grief, disgust, and despair (in either themselves or other people) have more inclination towards pedophilia. The inclination is small, but it is pronounced relative to things like love, safety, calmness, and eagerness.

The natural read is, of course, that pedophiles are more interested in uglier emotions. That might be true, but I have some uncertainty here.

For one thing, the numbers are small; on a scale from 0–5, average pedophilia goes from a bit under 0.1 for “Love” to 0.45 for “Grief” for men; for women, the range is about 0.01 to 0.14. That makes it hard to tell what this would look like if we’d conditioned on pedophiles: are people who identify as sexually aroused by children actually much more likely to enjoy the darker emotions?

But my real question is this: What is a pedophile?

The question Aella asked was how arousing children are. But as I said before, there are lots of reasons to answer yes to that: actual sexual attraction to young bodies, or a love of taboo, or wanting to be a kid, or enjoying power differentials, etc. etc. Is someone who likes taboo but isn’t attracted to kids’ bodies a pedophile? I don’t know… but they seem likely to answer yes to finding kids arousing, and to grief/disgust/despair. The same goes for people who like power differentials. This statistic might not be a result of “true” pedophiles at all, but rather those that have other reasons to find children arousing in some form.

(Then again, I’m an actual pedophile and I find all of these emotions interesting sexually, so I’m not exactly a good counter-example myself!)

So, say it with me now: This is complicated! [5]

It’s an interesting start, but it doesn’t answer the question just yet.

Assorted other comments where I can add context

Just collecting some miscellaneous thoughts here:

- Aella finds a bump among social conservatives who are also pedophiles. There was a time when this would’ve surprised me, but I’ve seen enough of them on some pedophile sites to have accepted it. I still don’t know why; I would’ve thought there’d be more of an orientation towards the LGBTQ side of progressivism. But I can imagine several mechanisms:

- Fear of government persecution: if you’re trying to find others like you and worried about law enforcement getting involved, or looking at either artificial or real child pornography and worried about being found out, I can see why you’d be more libertarian. (Libertarians are often associated with the “right,” although it’s unclear if that is a fit for marking yourself as socially conservative.)

- If you’re scared of your own desires, you might want greater social fabric in society that will keep “people like you” in check.

- Aella provides a chart on weight that shows that very light/small men have an increased average pedophilic attraction, as do very heavy/overweight men. (Yes, this ties into the “fat pedo” stereotype.) The push to the extremes might be an example of “weird correlates with weird.” I can also imagine other explanations: people who feel socially isolated due to their pedophilia might gain weight or take worse care of themselves and lose weight; pedophiles who don’t expect to date might also be less likely to worry about conforming to norms of attractiveness.

- Aella finds that there seems to be no particular effect of number of siblings; there might be an effect of birth order on pedophilic desire, where younger siblings are more likely to be pedophiles, but it might just be noise.

- One plausible explanation: older parents often have a higher rate of kids born with mental illnesses. The “number of siblings” effect might be a reflection of that: if you have many older siblings, you were likely born when your parents were older, and so mutations in their reproductive material might bring out pedophilia (as well as other differences).

- Here is another, much less palatable explanation, that I feel obligated to bring up in order to do a full analysis: More older siblings might provide more opportunity for sibling-on-sibling sexual assault… it’s ick, I feel bad for even mentioning it, but I don’t want to discard any hypotheses.

- Aella has a whole bunch of things that seem to correlate with pedophilia that might just correlate with (a) depression, or (b) the fact that having pedophilia genuinely does mean your life circumstances are probably a bit worse. (If for no other reason than it affects your dating life.) For example, pedophiles are more likely to answer affirmatively to “if life is a game, then I’m losing” and “I shirk my duties.”

- Pedophiles, and very specifically female pedophiles, seemed more likely to express less sympathy with others: they answered affirmatively to “I feel little concern for others” and negatively to “I sympathize with others’ feelings.” It’s hard to tell if this is something that is really about pedophilia or something else. For example, it could be people pitying themselves and feeling like the concerns of others feel more trivial in comparison; it could be related to depression as in the previous bullet point; or it could be a resurgence of weird correlates with weird (e.g. people who have pedophilia are a bit more likely to have a psychiatric condition that makes it harder to sympathize with others, but it’s not about the pedophilia per se). It could also be that the knowledge that other people would hate you if they really knew you makes you less likely to have sympathy with them. Honestly, these charts kind of freaked me out because it would be genuinely worrying if pedophiles are less likely to have sympathy for others, but the more I think about it, the more I’m unsure what to say. In particular, I have no idea why there’d be such a jump for women, unless it’s statistical noise. (Which is possible, since there are many fewer female pedophiles.) This would be another place where it’d be great to control for other factors, or subtract out those who indicated other mental illnesses.

- Pedophiles, again especially female pedophiles, experienced more sexual harassment. In particular, women who rated themselves as a 5 on a 0–5 scale for arousal from children also reported much more sexual harrassment. There are lots of possible underlying causes (weird correlates with weird; depression; etc.) but it could also be that women who are interested in children don’t show a typical response to male interest and so experience more harassment. This is total conjecture again; I have no special information.

- Finally, this is kind of ridiculous, but I’m very curious if pedophilia correlates with other fetishes and how. I’ve heard several people conjecture that foot fetishes appear in a higher fraction of pedophiles than in the general population; one person thought every pedophile has one, which is not true. This survey could provide a good way to get some data around such questions. I don’t know if it’s very important for research, but I sure am curious!

Wrapping up

Congratulations, you made it to the end of this massive post!

It may feel unsatisfying. All I did the whole time was poke holes—and that was with research I liked! I think what people often underestimate about social science is that it’s actually quite difficult to do well. Data can’t just be taken at face value; we have to dig in, consider alternatives, understand where it’s really coming from. Aella’s work has moved us closer to uncovering important truths. We have a long way to go, but I am so grateful for the work.

I have learned about myself, and about others like me. I’ve updated my view on what we’re like and how we work, and I’ve come up with a lot more questions I’d like to see researched. I hope others do the same, and that we can use this data to better understand and support pedophiles. Long-time readers of my writing know: that is the best way to safeguard everyone and help everyone be happy and thrive.

So let’s keep researching, let’s keep analyzing, and let’s keep being critical consumers of data.

Footnotes

[1]: Wikipedia deep dives I never expected to take while blogging about pedophilia: Biggest ball of twine.

Also, if you’re not from the US, you might never have heard of these things. But there are several towns around the US that claim to have assembled the world’s largest ball of twine, and become tourist highway stops for people doing long drives and interested in a distraction for a little while. This kind of random attraction along the road was best captured, I think, in Neil Gaiman’s book American Gods if you want a nice bit of Americana reading along with a rich and deep fantasy world.

[2]: Aella clarified by personal e-mail how to interpret the gender charts. Trans and cis people are identified by their genders; nonbinary people are identified by their sex at birth. In other words, assigned male at birth (AMAB) people are the red bar for cis and nonbinary, but the blue bar for trans. Hence, AMAB people are overrepresented as pedophiles among trans, cis, and nonbinary people. However, that overrepresentation is less among trans people.

[3]: As an aside, the specific question about perpetrating sexual assault is not as discerning as I might wish. Aella asked, “Have you ever had a sexual experience with someone else who did not want the experience?” with the options being, “No,” “Yes, slightly,” “Yes, significantly,” and “Yes, extremely.” These are open to broad interpretation. Are they talking about the kind of intercourse (e.g. touching vs penetration), the level of consent (“hard to say no to an authority figure” vs “too drunk to say no” vs “fighting back”), etc.? Unfortunately, I’m not sure there’s something better: my understanding is that coming up with the “right” question here is actually extremely difficult. So this result would be better phrased as: “those who reported that they perceived themselves as perpetrating a severe sexual assault were more likely to identify an attraction to children.”

[4]: When Aella subtracts out those who reported being sexually assaulted as children, the correlation between interest in pedophilia and age of first having sex mostly seems to go away. (I’m just eyeballing the chart here.) That actually implies that the measure of sexual assault is pretty good, and subtracting it out does give a clearer picture of how early sex and pedophilia are related.

[5]: In fact, one study researching how people react to young animals (with no sexual arousal) notes: “Currently, pedophilia is considered the consequence of disturbed sexual or executive brain processing, but details are far from known. The present findings raise the question whether there is also an over-responsive nurturing system in pedophilia.”

Note: I want to apologize for how few posts I’ve been making lately! I have felt neglectful of the blog, but the truth is that there has been a lot going on in my life outside of the blog and that has kept me busy. I put a lot of effort into each post, and so it takes me time to get them out with the quality I want to have. I do hope to keep up a faster pace, though, if life gives me the space to do so! In case you haven’t noticed, though, you can sign up for email updates on the blog. Sign up, and it’s like Substack, but without me ever asking you to pay anything. 🙂